Atlanta Through the Archives

Jackson Hill Disputes

Summary

Alarmed by the increasing integration of Atlanta, white home-owning residents

in Jackson Hill met in October 1910 to delineate a racial boundary line for their neighborhood,

starting a series of

informal policies, community meetings, social pressures, and, eventually, laws that promoted

segregation. Prior to this movement, there were no major moves towards systematic housing

segregation in Atlanta.

This led to Atlanta's first attempted zoning ordinance, dubbed the Ashley Ordinance after Councilman

Claude Ashley who politically spear-headed the disputes in Jackson Hill. This ordinance “forbade

blacks from occupying homes on white blocks and whites from occupying homes on black blocks unless

the majority of owners agreed that a house was open for occupancy by either whites or blacks.”

____________________________________________________________________

In 1910, Baltimore passed the nation’s first racial segregation ordinance. This ordinance came under

criticism by numerous groups nationwide, and such legislation was not immediately sought in Atlanta

due to these factors, like the impact on rental real estate.

Soon after, in Atlanta, there was a sudden “influx” of African Americans into what was once white or

less dense urban areas; white community leaders blamed either the new streetcar access or the

founding of Morris Brown College, a Black institution, in 1885 in the nearby area.

“According to reports by the Atlanta Constitution, the transfer of homes on Houston Street between

Jackson and Boulevard from whites to blacks spurred the movement of whites to demand strong action

on the part of the council.”

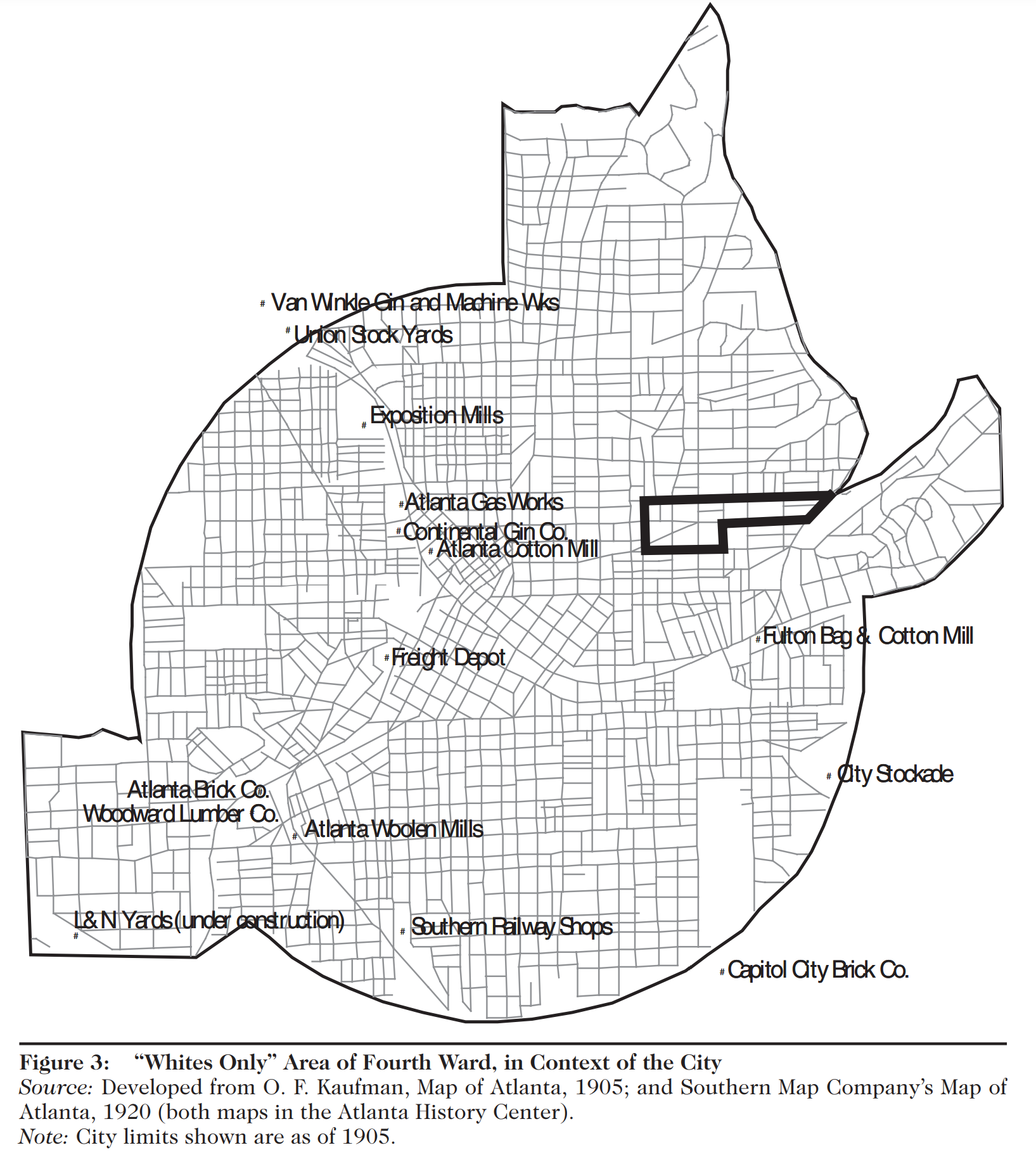

Consequently, later in that same year, the residents of Jackson Hill near lower Fourth Ward

organized and declared a racial boundary line, where no homes should be sold to black buyers. As

this first attempt at segregation was enforced only through social pressure, it was largely

unsuccessful.

However, the political pressure was successful; in 1913, the Ashley Ordinance was passed. This

ordinance “forbade blacks from occupying homes on white blocks and whites from occupying homes on

black blocks unless the majority of owners agreed that a house was open for occupancy by either

whites or blacks.”

“I have been out among the people of the lower part of the Fourth Ward every night for several weeks

imploring them to calm themselves and let council act. . . . I am afraid that unless this ordinance

is passed there will be trouble. . . . I’ll tell you frankly that I don’t want to go out there

tonight and tell the people that council would not relieve them” - Councilman Claude Ashley, sponsor

of the bill, referenced threats of violence to force action on residential segregation.

In the 1915 Carey v. Atlanta, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled the ordinance was unconstitutional, on

the basis that it restricts an owner’s right to freely exchange their property (Steil & Delgado

12).

Jackson Hill leaders turned again to informal agreements, creating a committee that met at

Westminster Presbyterian and made threats to do all within their power to uphold racial segregation.

This agreement encouraged the city to adopt its second segregation ordinance in 1916, copied from a

Louisville, Kentucy ordinance. It was upheld by the Georgia Supreme Court in 1917, with Justice P.

J. Evans writing that purpose of the ordinance is “in order to uphold the integrity of each race and

to prevent conflicts between them resulting from close association.” (Bishop Lands 105)

However, efforts for racial segregation were temporarily set aside due to the Great Fire in 1917; at

the same time, “the Supreme Court ruled Louisville’s segregation ordinance, and other cities’

ordinances by extension, unconstitutional in Buchanan v. Warley.” (Bishop Lands 97). This did not

prevent Atlanta from spatial segregation for long, by the 1920s Atlanta officials began to use

racial zoning maps to the same aim.

This was the first time after the abolition of slavery that systematic housing segregation was

proposed in Atlanta. Due to the political pressure applied by Jackson Hill residents, Atlanta

adopted a series of housing segregation policies, continuing to pass new ones as they were

overturned.

SOURCES:

Steil, Justin and Laura Delgado. “Contested Values: How Jim Crow Segregation Ordinances Redefined

Property Rights.”Global Perspectives in Urban Law: The Legal Power of Cities, edited by N. Davidson

and G. Tewari, Routledge, 2018, pp. 7-26.

Lands, LeeAnn Bishop. “A Reprehensible and Unfriendly Act: Homeowners, Renters, and the Bid for

Residential Segregation in Atlanta, 1900-1917.” Journal of Planning History 3, no. 2 (May 2004):

83–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513204264096.

Tags {zoning, racial segregation}

“I have been out among the people of the lower part of the Fourth Ward every night for several weeks

imploring them to calm themselves and let council act. . . . I am afraid that unless this ordinance is

passed there will be trouble. . . . I’ll tell you frankly that I don’t want to go out there tonight and

tell the people that council would not relieve them”

-Councilman Claude Ashley, sponsor of the Ashley Ordinance,

referenced threats of violence to force action on residential segregation.